The economy has boomed and exports have soared but vulnerabilities remain

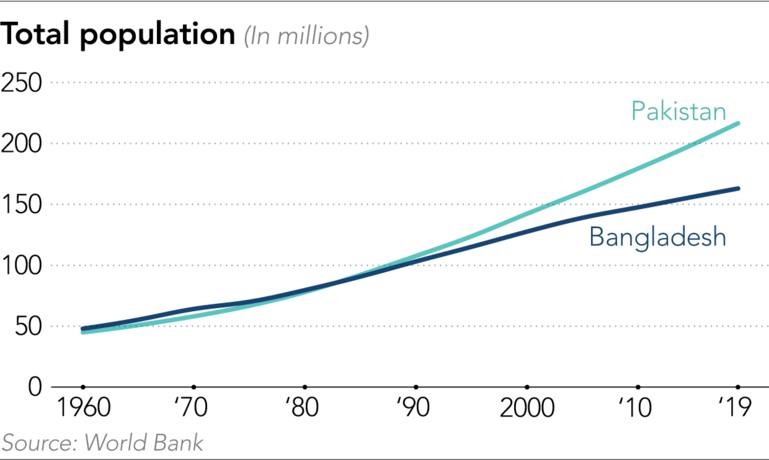

Bangladesh is marking the 50th anniversary of its independence from Pakistan today, buoyed by economic progress and relatively successful response to the coronavirus pandemic — but aware of the progress still needed to lift more of its 163 million people, 2% of the global population, out of poverty.

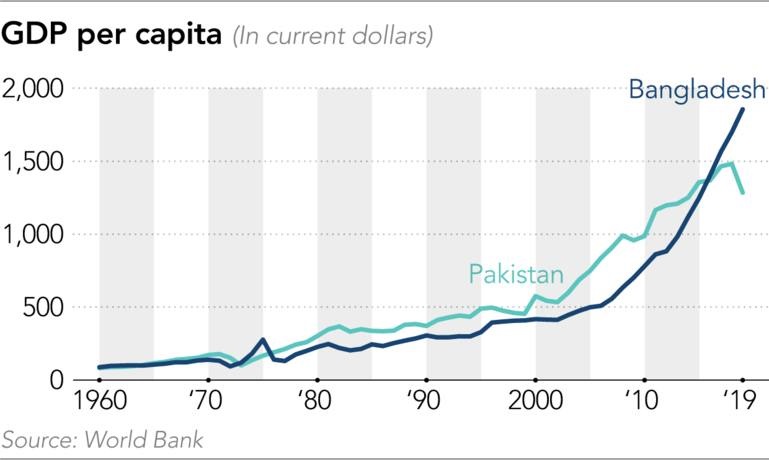

Since 1971, when Bangladesh became independent, it has outstripped Pakistan in generating growth, with apparel exports and a surge in remittances helping to drive the economy.

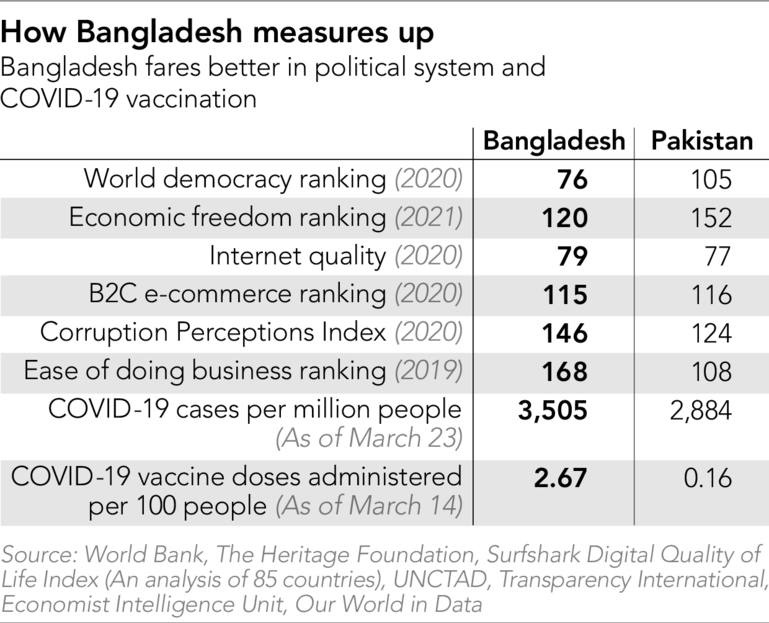

Bangladesh’s growth rate exceeded 8% in 2019, according to World Bank data. When the country seceded from Pakistan, its gross domestic product per capita was about three-quarters of Pakistan’s; by 2019, it was almost 45% more.

The country reached a lower middle-income country status in 2015 — defined by the World Bank as having gross national income per capita of between $1,036 and $4,045. The category also includes India, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Bangladesh is also on track to be moved out of the United Nation’s Least Developed Countries list in 2026.

Its economy has even exhibited resilience during the coronavirus pandemic, thanks to the government’s timely stimulus packages, and decided to reopen factories as early as May 2020. Meanwhile, remittance inflows from Bangladeshis working overseas reached $16.7 billion for the eight months starting from July 2020, the start of the country’s fiscal year, a third higher than total remittances of the same period in the previous year, according to Bangladesh Bank, the central bank.

One of the most densely populated countries in the world, Bangladesh has enjoyed a steady population growth over the years, though the growth rate is not as fast as that of Pakistan, and populations that were almost identical at independence have diverged sharply.

A young workforce and higher participation by women in the labor force have played a significant role in the country’s development, especially for its export-oriented labor-intensive garment industry. According to the World Bank, 36% of women aged 15 or over were economically active in Bangladesh in 2019, compared with 22% in Pakistan and 21% in India.

On the flip side, even though the share of the country’s population living below the national poverty line more than halved from 48.9% in 2000 to 21.8% in 2018, the large population base means that its government still needs to work harder to elevate standards of living for over 35 million people.

“A country with an abundant young and enterprising population needs to focus on developing skills and applicability,” Manmohan Parkash, country director for Bangladesh of the Asian Development Bank, told Nikkei Asia. “Within this, they also need to focus on women and youth,” he added.

Trade accounted for nearly 37% of Bangladesh’s GDP in 2019, compared with about 30% for Pakistan. The country’s export earnings are overwhelmingly reliant on its ready-made garment industry, with clothing products making up more than 80% by value, according to 2019 data from the World Trade Organization. That has grown from under 40% in 1990.

In contrast, the WTO data show that Pakistan’s exports are more diversified, with textiles being the largest product group (33%), followed by clothing (27%) and agricultural products (22%).

Parkash said Bangladesh needs to diversify its exports and that even within the garment sector, it should upgrade its output from low-value products to high-value ones to improve its profit margin.

Sanchita Saxena, director of Subir and Malini Chowdhury Center for Bangladesh Studies at UC Berkeley, said the country faces the paradox that the economic benefits brought by its garment industry are not shared by the country’s workers.

“The GDP measures something at the country level but it doesn’t necessarily get to how the average person is doing,” Saxena said, adding that garment workers are still earning very low wages and trapped in poor working conditions with no job security.

Foreign direct investment has reached Pakistan’s level in the past decade. Before the pandemic in 2019, soaring foreign investment had been giving an added push to Bangladesh’s booming economy as multinational companies, mainly from China and Japan, looked to harness its strong domestic demand.

Buoyed by investments, exports, and remittances, Bangladesh’s foreign-exchange reserves reached $32.7 billion in 2019, double those of Pakistan.

Parkash from the ADB said the country should update infrastructure, improve its financial sector and open up space for private businesses to attract more foreign capital, which is now less than 1% of its GDP.

“Bangladesh needs an open, transparent modern financial system that can embrace new technology… to attract investment, they must know how [to] get this money into the country [and] out of the country,” he said.

Bangladesh still depends heavily on foreign aid. It received about $5.5 billion in gross official development assistance in 2019. Almost one quarter came from Japan, its largest individual country donor, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The country has done relatively well in containing the coronavirus, with a lower case count per 1 million people than Japan, and it is pushing ahead with vaccination. But infections are resurging and the consequences from massive job losses increased poverty and lost exports during the pandemic are likely to unfold in the next few years.

Bangladesh’s political situation remains a concern. The Awami League-led government has resorted to more authoritarian approaches in recent years, cracking down on free speech, arresting critics, and granting impunity for abuses by security forces, according to Human Rights Watch.

Corruption, political instability, and the country’s vulnerability to climate change remain risks that could hold back development — while the country is also nervously eyeing events in Myanmar, after already receiving 1.1 million Rohingya refugees from across the border.